Imagine that every time you want to call your mother, instead of looking up her number in your contacts, you had to recompute it by analyzing all your past conversations, family photos, and childhood memories. Absurd, right? Yet that’s exactly what AIs like ChatGPT do to retrieve simple facts like “Paris is the capital of France”.

Executive summary

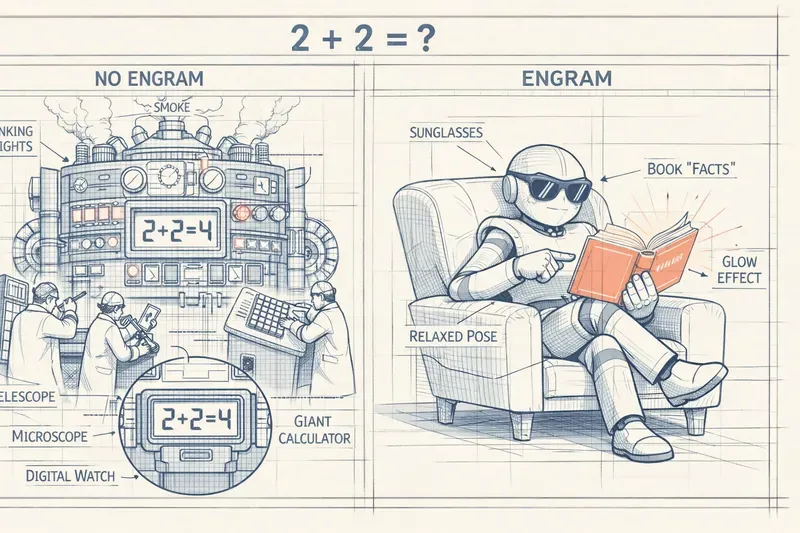

Observation: an LLM spends a lot of compute “retrieving” simple facts (e.g., a capital), as if it had to re-derive them every time.

Engram’s idea (DeepSeek): add an external memory — a “directory” — to perform very fast lookups for certain patterns (N-grams).

Key mechanism: a gate decides when to consult the directory, to avoid irrelevant/out-of-context lookups. Less energy wasted, and more compute budget available for reasoning and long contexts.

Limits: fact updates, ambiguity (multiple meanings), and the size/quality trade-off of the directory.

Glossary

- Transformer

- neural network architecture (at the core of LLMs) combining attention and feed-forward layers, used to process token sequences.

- Parameters

- learned “weights” during training (often billions) that determine the model’s behavior.

- Context / context window

- : the portion of text the model can “see” at once (the conversation/document in input).

- N-gram

- contiguous sequence of (N) tokens (e.g., “capital of France”) used here as a recognizable pattern.

- Hash

- numeric fingerprint of a sequence, used to retrieve an entry quickly in a table (barcode analogy).

- Lookup

- direct retrieval of information via a key (here, the hash of an N-gram), instead of “recomputing” through the entire network. (O(1)) : “constant” time (in practice very fast): lookup time does not grow with the directory size at these orders of magnitude.

- Gating (gate / guard)

- mechanism that decides whether the model should consult external memory (the directory) given the context.

- Hash collisions

- cases where two different sequences produce the same fingerprint; typically mitigated with hashing/storage strategies.

The problem: a supercomputer to remember a phone number

When you ask ChatGPT “What is the capital of France?”, here’s what happens inside:

Your question goes through dozens of layers of ultra-complex computations. Each layer contains billions of connections that activate, weigh, and adjust. It’s like mobilizing a whole team of engineers, mathematicians, and physicists… to retrieve a phone number you already know by heart.

The waste is massive. Billions of operations, phenomenal power, all to recover a static fact — information that doesn’t change: Paris = capital of France. It’s like using an electron microscope to read the time on your watch.

And it’s not just about elegance. This waste has real consequences:

- The AI is slower to respond

- It consumes a lot of energy

- It has less “room” for complex reasoning

- It costs more to run

The (simple) idea: an instant directory

DeepSeek researchers had a simple but powerful idea: what if we gave the AI a directory?

Imagine a separate, ultra-fast module that contains simple facts in a format that’s easy to search. When the AI sees “capital of France”, instead of mobilizing 70 billion parameters, it glances at the directory and instantly finds “Paris”.

They called this system Engram (from “engram”, the physical trace of a memory in the brain). The core principle: separate “remembering” from “thinking.”

Here’s how it works in practice.

The magic directory in action

Step 1: Split into recognizable chunks

Take the sentence: “The capital of France is Paris.”

The AI breaks it into small groups of words called N-grams (“N” just means “several”). For example:

- “The capital of”

- “capital of France”

- “of France is”

- “France is Paris”

It’s like splitting a phone number into segments: 01-23-45-67-89.

Step 2: Create a unique fingerprint

For each segment, Engram computes a digital fingerprint (a “hash”, in technical jargon). It’s like turning “capital of France” into a unique barcode: #47291.

That fingerprint enables ultra-fast retrieval in constant time (what computer scientists call (O(1)) — but the key idea is: instant, regardless of the directory size).

Step 3: Store it in the directory

Fingerprint #47291 points to a small data packet saying: “When you see this sequence, the most likely continuation is ‘Paris’.”

It’s stored in a compact structure — more like a book index than the entire book.

Step 4: The gatekeeper

Here’s the subtle part: the AI does not blindly consult the directory on every token.

It has a “gatekeeper” (technically: contextual gating) that decides: “Should I consult the directory here, or do I truly need to think?”

Example where consulting the directory makes sense:

- “The capital of France” → lookup → “Paris” (static fact)

Example where you should NOT consult it:

- “If France became a monarchy, its capital…” → reasoning needed, not a lookup

The gatekeeper helps avoid stupid errors, like looking up “capital” in a metaphorical context (“Paris is the capital of fashion”).

The gains

More room to think

By delegating simple facts to the directory, the AI’s neural layers are freed up. They can focus on what they do best: reasoning, creating, analyzing.

It’s like offloading phone numbers from your head into your contacts and suddenly having more mental space for complex problems.

Measured result: On reasoning tasks (math, logic), models with Engram perform better than equivalent models without Engram, even with fewer total parameters.

Longer texts

One major challenge for modern AIs is handling very long contexts (hours-long conversations, documents with hundreds of pages).

Every additional token costs compute. But if a meaningful fraction of those tokens correspond to simple facts retrievable via lookup, the cost drops sharply.

Measured result: Engram enables processing contexts 2–3× longer for the same compute budget.

Less energy wasted

A directory lookup consumes thousands of times less energy than a full forward pass through tens of billions of parameters.

At the scale of millions of users, that’s the difference between a power plant and a light bulb.

A concrete end-to-end example

Take this question: “What is France’s GDP in 2023 and how does it compare to Germany’s when accounting for population?”

Without Engram (classic method):

- The AI goes through all its layers to retrieve “France GDP 2023” → ~€3,000B

- The AI goes through all its layers to retrieve “Germany GDP 2023” → ~€4,000B

- The AI goes through all its layers to retrieve “France population” → ~68M

- The AI goes through all its layers to retrieve “Germany population” → ~84M

- Finally, it uses reasoning to compute per-capita GDP and compare

Steps 1–4 are pure compute waste.

With Engram:

- Instant lookup: France GDP = 3,000B

- Instant lookup: Germany GDP = 4,000B

- Instant lookup: France population = 68M

- Instant lookup: Germany population = 84M

- All compute budget goes into reasoning: divide, compare, write a nuanced answer

The payoff: the neural layers can do finer reasoning, consider more nuance, because they haven’t burned their “budget” on fact retrieval.

The real innovation: the balance

Engram’s genius isn’t just having a directory. It’s finding the right balance between:

- Static memory (the directory): fast, compact, for facts

- Dynamic reasoning (neural layers): slower, expensive, for thinking

Before Engram, everything went through reasoning. That’s like using your conscious brain to breathe — technically possible, but exhausting and inefficient.

With Engram, the AI gains a reflex system for simple tasks, freeing its “conscious brain” for what really matters.

What it changes for you

If you use an AI with Engram (like future DeepSeek models):

You’ll see faster answers for factual questions. No need to mobilize an army of neurons to recall “Paris is the capital of France.”

You can have longer conversations without the AI “forgetting” the beginning. Long context becomes cheaper.

You’ll get deeper reasoning on complex questions. The AI no longer wastes its budget on useless lookups.

Concrete example: ask the AI to analyze a 50-page contract. With Engram, it can:

- Instantly retrieve standard legal definitions (lookup)

- Spend its reasoning budget on the specific clauses, implications, and risks

Limits and open questions

When the directory is wrong

What happens if a fact changes? If “capital of France” suddenly becomes Lyon (unlikely, but play along)?

Engram’s directory is static: it is built during model training. Updating it requires retraining or dedicated update techniques (not detailed in the original paper).

That’s a trade-off: speed vs freshness.

Directory size

An infinite directory is useless (too slow to search). A tiny directory would miss important facts.

Researchers found that a directory representing about 10% of the model size was optimal. For a 7B-parameter model, that’s ~700M entries in the directory.

Ambiguous facts

“Bank of France” can refer to the financial institution — or the “river bank” in France (rare, but possible).

The contextual gate must be smart enough to avoid dumb lookups. This balance remains an active research area.

Deliberate teaching simplifications

To keep this article accessible, I intentionally simplified several technical aspects:

What I simplified

The “contextual gate” is far more sophisticated than a simple guard. It’s a neural network trained to predict when a lookup will help, based on subtle context signals. I used the “gatekeeper” metaphor to avoid diving into attention and gating mechanics.

Hash collisions: two different sequences can theoretically produce the same fingerprint. The paper uses collision-resolution techniques (like multiple hashes), but I omitted that detail to keep things readable.

Vocabulary compression: Engram actually uses a compressed vocabulary to reduce directory size. I presented it as “a compact data packet” without diving into tokenization details.

Integration into transformers: I said the lookup “frees up the neural layers”, but technically Engram integrates between certain transformer layers, not simply “next to” the model. Explaining that nuance would have required a deeper architectural detour.

Why these simplifications are OK

The essence is still true: Engram does separate static memory from dynamic reasoning. The directory metaphor captures this well.

The gains are real: the figures cited (2–3× longer contexts, reasoning gains) come from the original paper’s benchmarks.

Pedagogy matters: explaining hash collisions before explaining why you hash at all would kill intuition. I chose to build the mental model first.

What remains correct despite the simplifications

- Lookup in (O(1)) via hashing

- The memory vs reasoning distinction

- Measured gains in efficiency and long-context handling

- Existence of a contextual gating mechanism

- Speed vs freshness trade-off

Going further

Open question: if we push this idea to the extreme, could we imagine an AI with multiple specialized “directories”? One for geography, one for historical dates, one for math formulas?

Connection to other concepts: Engram echoes external memories in neuroscience (like your address book), but also caches in computing (ultra-fast memory for frequently used data).

Future implications: if this approach generalizes, we may see much more modular AIs: a central “brain” for reasoning, and specialized peripheral modules for different knowledge types — somewhat like the human brain, with dedicated areas for language, vision, motor control…

Ethical question: who decides what goes into the directory? “Paris is the capital of France” is obvious, but what about controversial or politically charged “facts”? Does the directory encode biases?

Web resources

- Original paper (arXiv): Engram Conditional Memory via Scalable Lookup: A New Axis of Sparsity for Large Language Models

- Official source code (GitHub): deepseek-ai/Engram

- AICybr complete guide: DeepSeek Engram Complete Guide

- Analytics Vidhya analysis: DeepSeek Engram

In short: Engram upgrades AIs by giving them what we all have in our pocket: a directory. Instead of recomputing “Paris is the capital of France” every time, the AI can finally just… remember. And this simple distinction — remembering vs thinking — might be the key to faster, more efficient, and ultimately smarter AIs.

AiBrain

AiBrain