Related articles: LLM Recipe GPT Style: architecture explained | Embeddings: how AI does math with words

Executive Summary

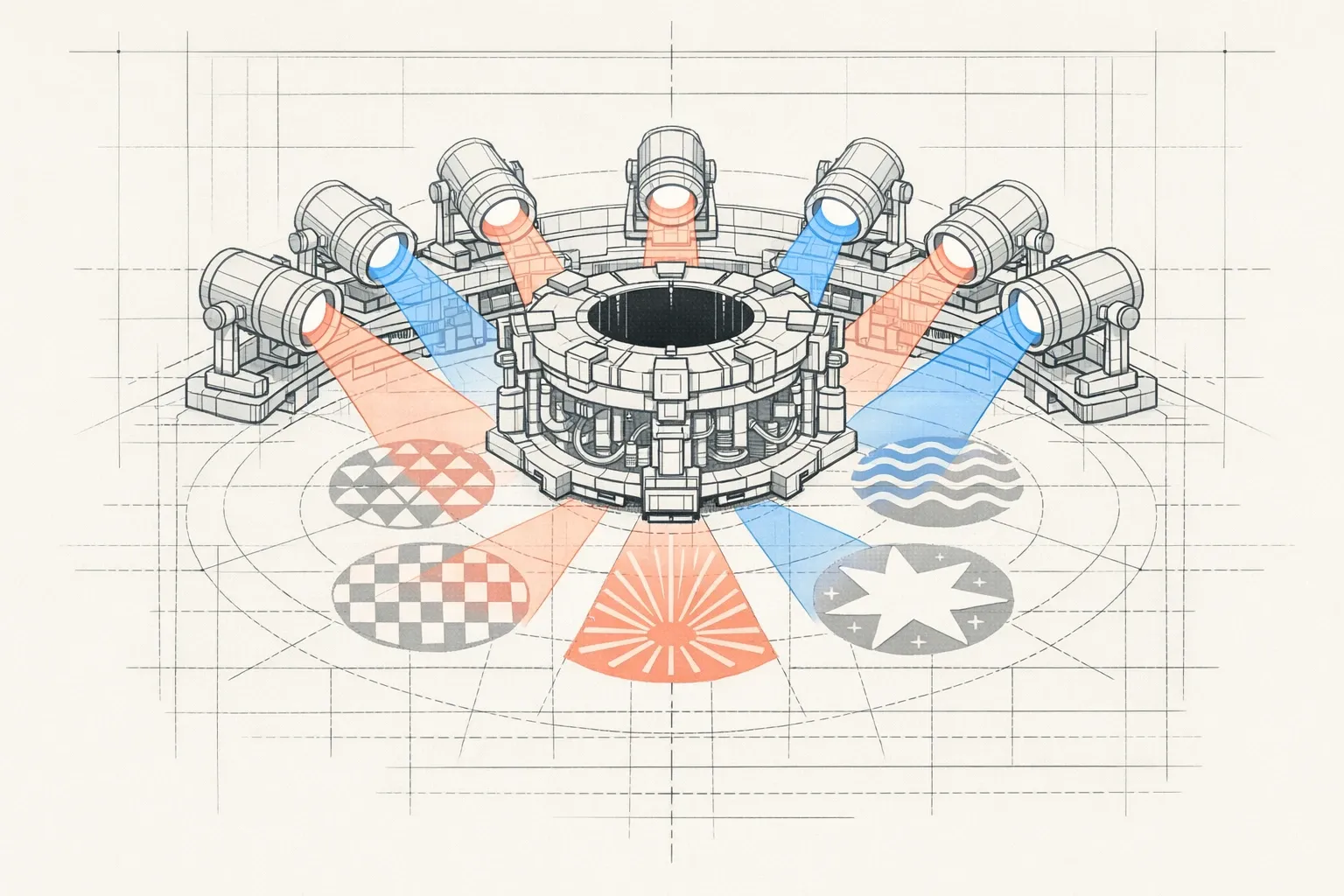

This article demystifies multi-head attention, the core mechanism of Transformers like ChatGPT, through the metaphor of 8 projectors simultaneously illuminating a sentence from different angles: syntax, pronouns, causality, semantics…

The problem: A single attention mechanism cannot simultaneously capture all the multidimensional relationships of language (grammar, meaning, references, logic). It’s like trying to illuminate a complex scene with a single spotlight.

The solution: Multi-head attention uses multiple attention “heads” in parallel (12 heads for GPT-2, up to 96 for GPT-3, 32-64 for LLaMA 2, or 12 for BERT-base). Each head spontaneously specializes during training in a specific type of linguistic relationship, working independently like experts in their field.

The result: The representations from each head are merged to create a rich, multidimensional understanding. For example, GPT-2 uses 12 heads, GPT-3 up to 96 heads, allowing LLMs to “see” your message from all angles simultaneously.

Key points:

- Parallel processing: all heads analyze simultaneously, not sequentially

- Emergent specialization: each head naturally discovers its area of expertise

- Intelligent fusion: results are concatenated and harmonized for complete understanding

- Proven efficiency: multiple specialized heads are better than a single very powerful head

This article explains these concepts with pedagogical simplifications, while clarifying technical nuances and providing resources for deeper learning.

Glossary: Understanding Technical Terms

- Multi-Head Attention

- : Core mechanism of Transformers using multiple attention “heads” in parallel to simultaneously capture different types of linguistic relationships (syntax, semantics, references, causality, etc.). Each head analyzes the sentence from a specific angle, then the results are merged.

- Transformers

- : Neural network architecture introduced in 2017 (paper “Attention Is All You Need”) that relies on the attention mechanism instead of RNN/LSTM. This architecture is the foundation of all modern LLMs like GPT, Claude, Llama.

- QKV (Query/Key/Value)

- : Three linear projections used in attention computation. Query: what each word seeks as information. Key: what each word offers as information to others. Value: the concrete information transmitted by each word. Attention compares Queries with Keys to determine how to combine Values.

- Softmax

- : Mathematical function that transforms raw attention scores into normalized probabilities (summing exactly to 1). It converts numerical scores into interpretable attention weights.

- Attention heads

- : Independent units in the multi-head mechanism. Each head computes its own attention in parallel. Dimensions vary by model (e.g., 64 dimensions per head for a total of 512 with 8 heads). The outputs of all heads are concatenated then transformed.

- LLM (Large Language Model)

- : Large-scale language models like GPT-3/4, Claude, Llama, trained on billions or trillions of words to predict and generate text. They use the Transformer architecture with multi-head attention.

- Emergent specialization

- : Phenomenon where each attention head spontaneously develops expertise in a specific type of linguistic relationship (pronouns, syntax, named entities, etc.) during training, without explicit instruction.

- Concatenation

- : Operation that joins together the representations of all attention heads to create an enriched, multidimensional representation of the text.

When you write “The bank refused my loan because it was too cautious”, how does an LLM know that “it” refers to the bank and not you? And how does it simultaneously understand that “bank” is a financial institution, that “cautious” describes this institution, and that “because” introduces an explanation? A single attention mechanism might miss these nuances. That’s why large language models use something more powerful.

Imagine a crime scene plunged into darkness. A single spotlight could illuminate clues one by one, but you’d miss crucial connections. Now, imagine 8 different spotlights, each oriented at a unique angle, simultaneously revealing footprints on the ground, splatters on the wall, reflections on metallic surfaces, suspicious shadows. This is exactly what multi-head attention does: it illuminates your sentence from multiple angles at once, each revealing a different aspect of meaning.

The Problem A Single Spotlight Cannot Solve

Let’s revisit our sentence: “The bank refused my loan because it was too cautious.”

A simple attention mechanism (a single spotlight) must make difficult choices. It can focus on:

- Grammatical relationships: “it” is the subject of “was”

- Reference links: what word exactly does “it” refer to?

- Semantic context: “loan” + “refused” indicate a banking context

- Causal relationships: “because” establishes a cause-effect link

But here’s the problem: it cannot analyze everything with the same intensity at the same time. It’s like trying to simultaneously look at a painting’s shape, its colors, its composition, and the details of each corner with a single focused gaze. You must choose where to direct your attention, and you necessarily lose information.

Human sentences are multidimensional structures. Each word maintains multiple types of relationships with other words: syntactic (grammar), semantic (meaning), referential (pronouns), causal (logic). To truly “understand”, a model must capture all these dimensions simultaneously.

The Solution: 8 Projectors Working In Parallel

Multi-head attention solves this problem with remarkable elegance: instead of a single attention mechanism, the model uses several in parallel. In GPT-2, that’s 12 heads (12 projectors). In GPT-3, up to 96. Each head is an independent projector that illuminates the sentence in its own way.

Let’s take 8 heads for our example. Here’s how they might specialize on our sentence:

Projector 1 (basic syntax): Intensely illuminates “The bank” → “refused”. It captures the immediate subject-verb relationship. Its beam is concentrated on basic grammatical structure.

Projector 2 (objects and complements): Illuminates “refused” → “my loan”. It understands that “loan” is the direct object of the refusal. Its angle reveals what undergoes the action.

Projector 3 (pronoun resolution): Illuminates “it” → “The bank”. This is its expertise: it systematically seeks what pronouns refer to. Its beam links “it” to its referent.

Projector 4 (semantic context): Illuminates a triangle between “bank”, “loan”, and “refused”. It detects the coherent semantic field of finance. Its broad lighting reveals the general theme.

Projector 5 (causal relationships): Illuminates “refused” → “because” → “was cautious”. It follows cause-effect logic. Its beam traces reasoning links.

Projector 6 (attributes and qualities): Illuminates “cautious” → “it” (thus “bank”). It understands that “cautious” describes a characteristic of the bank. Its angle reveals entity properties.

Projector 7 (possession): Illuminates “my” → “loan”. It captures possession and ownership relationships. Its beam is specialized in possessive determiners.

Projector 8 (global coherence): Illuminates the entire sentence with a broad beam. It verifies that all elements form a coherent whole.

Each projector (each attention head) works independently. They don’t consult each other during their analysis. It’s like 8 experts in a room, each taking notes on their specialty, without talking to others. This independence is crucial: it allows the model to process all these aspects in parallel, simultaneously.

How The Beams Combine To Create Understanding

Once the 8 projectors have finished their work, the model must merge all these observations into a single rich and nuanced understanding.

Imagine that each projector produced a detailed report on the word “it”:

- Projector 1: “Subject of the verb ‘was’, clear syntactic position”

- Projector 2: “No associated direct object”

- Projector 3: “Reference to ‘The bank’ with 98% confidence”

- Projector 4: “Financial context maintained, coherent”

- Projector 5: “Cause of the refusal action”

- Projector 6: “Possesses the attribute ‘cautious’”

- Projector 7: “No possession relationship”

- Projector 8: “Coherent with the rest of the sentence”

The model concatenates (joins end to end) all these reports. If each projector produces a 64-dimensional representation (64 numbers describing what it saw), then 8 projectors produce 8 × 64 = 512 dimensions.

This enriched representation of “it” now contains all the nuances: its syntactic function, its referent, its role in causality, its attributes. It’s like having a high-resolution 3D map with multiple layers of superimposed information, instead of a simple 2D sketch.

This fusion doesn’t happen randomly. The model learns during training how to weight and harmonize these different perspectives. Some information is amplified, others attenuated, depending on what’s most useful for understanding the context or predicting the next word.

Why Multiple Projectors Are Better Than One Very Powerful One

You might wonder: why not a single ultra-powerful 512-dimensional projector instead of 8 small ones of 64 dimensions each?

The answer lies in specialization and learning efficiency.

Imagine you had to simultaneously learn to play piano, paint portraits, and solve differential equations. Your brain would try to mix everything, and you’d progress slowly in all three domains. Now, imagine three people, each focusing exclusively on one domain. In the end, the collective team is much more competent, and each member becomes a true expert.

This is exactly what happens with attention heads. During model training on billions of words, each head spontaneously discovers that it can become better by specializing in a particular type of relationship. No one explicitly tells them “You, handle syntax, you handle meaning”. This specialization emerges naturally because it’s the most effective strategy for minimizing model error.

Researchers have analyzed models like BERT and GPT after training and discovered fascinating specializations:

- Some heads focus almost exclusively on pronouns and their referents

- Others detect relationships between nouns and adjectives

- Some capture long-distance dependencies (beginning and end of sentence)

- Others specialize in named entities (people, places, organizations)

This emergent division of labor is one of the main reasons transformers work so remarkably well.

The Complete Journey Of A Word Under The Projectors

Let’s follow the word “it” from start to finish on its journey through multi-head attention:

Step 1: Preparation (initial encoding)

The word “it” arrives with its initial numerical representation: a vector of 512 numbers encoding its position in the sentence, its identity, and some basic context. Think of it as the GPS coordinates of the word in the multidimensional space of language.

Step 2: Multiplication of perspectives

This unique representation is sent simultaneously to the 8 attention heads. It’s as if you took a photo and gave it to 8 different photographers, each with a different filter on their camera.

Each head transforms this representation according to its own perspective. The head specialized in pronouns will transform it to better detect referents. The syntactic head will transform it to better see grammatical relationships.

Step 3: Selective illumination (the heart of attention)

Now comes the magic. Each head looks at all the other words in the sentence and decides which are important for understanding “it” in its specialty domain.

- Head 3 (pronouns) decides: “The bank” is crucial (95% attention), “my” is somewhat useful (5%), the rest is negligible.

- Head 1 (syntax) decides: “was” is crucial (90%), “cautious” is useful (40%).

- Head 5 (causality) decides: “because” is crucial (85%), “refused” is very useful (70%).

Each head thus creates an attention map: a set of weights indicating where it pointed its projector and with what intensity.

Step 4: Creation of the new enriched representation

Based on this attention map, each head creates a new representation of “it” that incorporates information from words it judged important.

Head 3 produces a representation of “it” that essentially says: “I am a singular feminine pronoun that refers to ‘The bank’.”

Head 1 produces: “I am the grammatical subject of ‘was’ and I am associated with the adjective ‘cautious’.”

And so on for the 8 heads. Eight different representations, eight complementary perspectives.

Step 5: Fusion and synthesis

These 8 representations (8 × 64 = 512 dimensions) are joined end to end like train cars. This long representation then passes through a final transformation that harmonizes and compresses it if necessary.

Final result: “it” now has a representation that encodes:

- Its exact referent (the bank)

- Its grammatical function (subject)

- Its role in causality (agent of caution)

- Its attributes (cautious)

- Its coherence with the financial context

All this in a single vector of numbers, ready to be used for further processing or to predict the next word.

What You’ve Understood

You now know how an LLM can simultaneously understand all aspects of a complex sentence. Multi-head attention is:

- Multiple attention mechanisms in parallel (the projectors), each with its own angle of view

- Each spontaneously specializes during training in a type of linguistic relationship

- All work simultaneously, making processing fast and efficient

- Results are merged to create a rich, multidimensional, and nuanced understanding

Next time you chat with ChatGPT or another LLM, imagine these multiple projectors (8, 12, or even 96 depending on the model) scanning each word of your sentence. Each seeks something different: one tracks pronouns, another analyzes grammar, a third detects logical relationships. Together, they create that impression of “understanding” that makes these models so impressive.

Pedagogical Simplifications: What You Need To Know

I’ve deliberately simplified several technical aspects to make the concept accessible to a complete beginner. Here’s exactly what was simplified and why it’s acceptable for your understanding.

1. Query, Key, Value (QKV) Projections

What I said: Each head “transforms the representation according to its own perspective”.

The technical reality: Each head actually creates three different versions of each word via learned projection matrices:

- Query: what the word seeks as information

- Key: what the word offers as information to others

- Value: the concrete information the word transmits

Attention is computed by comparing a word’s Query with the Keys of all other words. Attention scores then determine how to combine Values.

Why my simplification is acceptable: Understanding QKV requires matrix mathematics (matrix products, linear transformations). The essential idea remains true: each head transforms words to extract certain relationships according to its specific angle. The projector metaphor with its “angle of view” captures this idea of oriented transformation well, without requiring the underlying mathematics.

2. Attention Computation (softmax and dot product)

What I said: Each head “decides” which words are important and assigns attention percentages (like 95%, 5%).

The technical reality: Attention is computed via:

- A dot product between the target word’s Query and the Keys of all words

- A division by √d (where d is the dimension) to stabilize gradients

- A softmax function that transforms scores into probabilities summing exactly to 100%

The mathematical formula: Attention(Q, K, V) = softmax(QK^T / √d) V

Why my simplification is acceptable: The final result is indeed a set of weights (probabilities) indicating the relative importance of each word. Whether these weights are computed via softmax or another method is less important than the fundamental concept: some words receive more attention than others, and these weights determine how information is combined. The percentages I gave (95%, 5%) are illustrative examples of the type of distribution softmax produces.

3. Head Specialization

What I said: Each head clearly specializes in a precise type of relationship (pronouns, syntax, causality, etc.), with very clear examples.

The more nuanced reality: Head specialization is real but often fuzzier and less categorical than my examples. A head can partially capture multiple types of relationships. Moreover:

- Specialization varies by layer (early layers capture simpler patterns, later layers more abstract relationships)

- Some heads appear redundant or poorly specialized

- Specialization isn’t programmed but emerges statistically from training

Why my simplification is acceptable: Scientific studies have indeed shown that specializations emerge. My examples are idealized archetypes that help understand the principle. The essential remains scientifically correct: having multiple heads allows capturing different types of linguistic patterns simultaneously. I could have said “a head tends to partially specialize in…” but that would have weighed down the text without adding to conceptual understanding for a beginner.

4. Number of Heads and Dimensions

What I said: 8 heads as the main example, each producing 64 dimensions (8 × 64 = 512).

The variable reality: The number of heads and dimensions varies enormously by model:

- GPT-2 small: 12 heads, total dimension 768 (so 64 per head)

- GPT-3: 96 heads, total dimension 12,288 (so 128 per head)

- BERT-base: 12 heads, total dimension 768

- LLaMA 2: varies by size (32 to 64 heads)

The number of heads is an architectural hyperparameter chosen by designers.

Why my simplification is acceptable: I chose 8 heads and 64 dimensions because:

- 8 is large enough to show diversity, not too large to lose the reader

- 8 × 64 = 512 is a simple calculation that illustrates concatenation

- The principle remains identical regardless of number: multiple heads in parallel, concatenation of results

The exact numbers matter little for understanding the fundamental concept.

5. Final Fusion and Output Transformation

What I said: The 8 representations are “joined end to end” then “harmonized” by a final transformation.

The technical reality: After concatenation, there’s a multiplication by a weight matrix W^O (the output matrix). This matrix is also learned during training. It doesn’t just “compress” or “harmonize”: it reorganizes, reinterprets, and combines information from different heads optimally for the task.

Why my simplification is acceptable: The concept of concatenation followed by transformation is correct. I omitted mathematical details (matrix multiplication, weight learning) because they don’t add to conceptual understanding for a beginner. The idea that “information is intelligently merged” captures the essence.

6. Head Independence

What I said: Heads work “independently” without consulting each other.

The nuance to add: This is true within the same layer: heads compute their attention in parallel without direct interaction. But in a deep model with many stacked layers, heads in one layer receive outputs from heads in the previous layer. There’s thus a form of indirect collaboration across layers.

Why my simplification is acceptable: To understand the multi-head mechanism, it’s enough to understand that heads in the same layer work in parallel. Interaction between layers is an additional level of complexity not necessary to grasp the basic concept.

What Remains Rigorously Exact

Despite these pedagogical simplifications, these points are scientifically correct:

✓ Multiple heads compute their attention in parallel (truly simultaneous, not sequential)

✓ Each head computes its attention independently within its layer

✓ Outputs are concatenated then transformed by a learned matrix

✓ Heads develop specializations during training (even if sometimes fuzzy)

✓ This mechanism allows capturing multiple types of relationships simultaneously

✓ It’s more efficient than a single head of equivalent size (empirically proven)

✓ The number of heads is an important architectural choice

Going Further: Open Questions

Now that you understand multi-head attention, here are some fascinating questions researchers are asking:

How many heads is truly optimal? Too few and the model lacks nuance. Too many and they become redundant, wasting memory and computation. Recent studies show we can sometimes remove 20-30% of heads without major performance loss. Why do some heads seem useless? How to identify critical heads?

Do heads really learn different things? Or do some perform redundant computations? Researchers have created visualization tools (like BertViz) that show what each head “looks at”. Sometimes patterns are clear (a head systematically follows pronouns), sometimes it’s more mysterious.

Can we control what heads learn? Instead of letting specialization emerge randomly, could we force certain heads to specialize in precise tasks? Some researchers experiment with “guided heads” to improve performance on specific tasks.

What happens in deep layers? Early layers of a model capture simple patterns (adjacent words, basic syntax). Later layers capture more abstract relationships (inferences, reasoning). How does this hierarchy build across the 24, 48, or 96 layers of a large model?

Does multi-head attention exist in the human brain? Our visual system indeed uses parallel “channels” (shape, color, movement, depth) that are then integrated. Is there a parallel with language processing in the brain? Can neuroscience and AI illuminate each other?

Web Resources

- Understanding and Coding Self-Attention, Multi-Head Attention - Sebastian Raschka

- Tutorial on Transformers and Multi-Head Attention - UvA Deep Learning

- Transformer Explainer - Interactive Visualization

- The Illustrated Transformer - Jay Alammar

- Multi-Head Attention: Deep Dive - Dive into Deep Learning

- Attention Is All You Need - Original Paper (2017)

AiBrain

AiBrain