Executive Summary

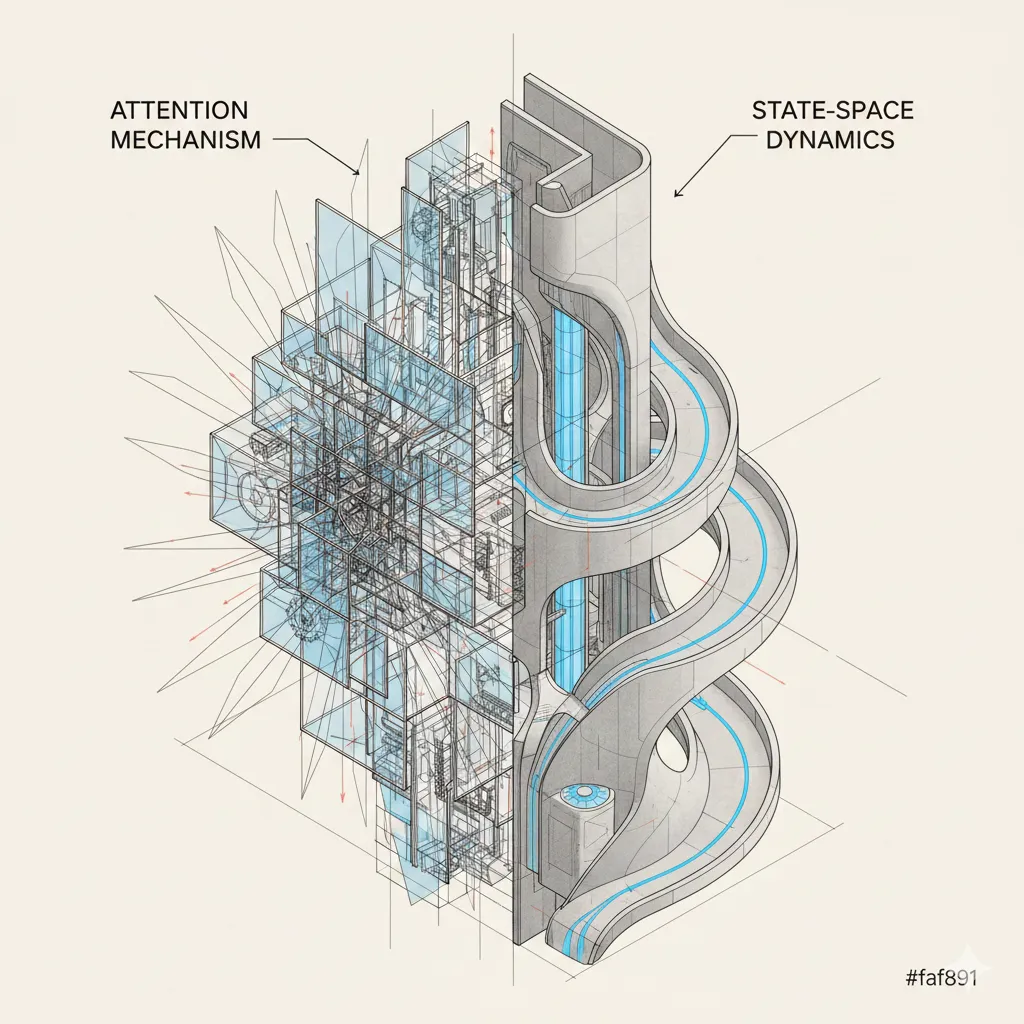

The Context : Since 2017, the Transformer attention mechanism has reigned supreme, powering the LLM revolution. Yet, despite its power, its GPU memory cost (the infamous KV cache) becomes an insurmountable bottleneck for very long contexts. Alternatives like State-Space Models (SSM) existed in the lab, but until now remained unable to match Transformer accuracy.

The 2025 Breakthrough : The landscape is changing. We’re moving out of the “Transformer for everything” era and into that of hybrid architectures.

-

Massive hybridization: Models like Jamba or Bamba now fuse Attention and SSMs, offering up to 3x higher inference throughput while handling 256k token windows.

-

Internal optimization: Gated Attention (Best Paper NeurIPS 2025) proves that the classic architecture can still be simplified and stabilized with minimal modifications.

The Stakes : This isn’t the death of Transformers, but the end of their monopoly. In 2025, architecture choice becomes a strategic decision: prioritize hybrid efficiency for mass processing, or pure Transformer robustness for critical reasoning and code.

Glossary: Understanding Technical Terms

- Transformer / Attention

- Neural network architecture introduced in 2017 that uses an attention mechanism to understand relationships between words in a sequence. Attention allows the model to “look at” all previous tokens to generate the next one. It’s the foundation of GPT, Claude, Llama, and most current LLMs. Attention is powerful but memory-intensive: it must store the complete sequence history.

- SSM (State Space Model)

- Alternative architecture to Transformers that models sequences via a constant hidden state rather than a complete history. Instead of storing all previous tokens in memory, an SSM maintains a compressed state that evolves sequentially. Advantage: linear complexity in sequence length (vs quadratic for attention). Disadvantage: loss of explicit access to the complete history.

- Mamba

- Specific SSM architecture developed in 2023 that uses selection mechanisms to decide which information to keep in the hidden state. Mamba-2 is an improved version. These models excel on very long sequences (256k+ tokens) but struggle on tasks requiring precise recall of distant information.

- KV Cache (Key-Value)

- Storage mechanism used by Transformers during generation. For each generated token, the model computes and stores key-value pairs that represent contextual information. This cache grows linearly with sequence length, which limits context size. SSMs don’t need this cache, hence their memory advantage.

- Gated Attention

- Innovation awarded Best Paper Award at NeurIPS 2025. Adds a sigmoid gate after each attention head to introduce nonlinearity and sparsity. Reduces “attention sinks” (tokens that artificially accumulate attention) and improves training stability. Minimal modification that easily integrates into existing Transformers.

- Mixture-of-Experts (MoE)

- Architecture where only certain “experts” (sub-networks) are activated for each token, reducing computational cost. A 52 billion parameter model may have only 12 billion active at inference. Used in Jamba and other hybrid models to combine efficiency and capacity.

- In-context learning

- Model’s ability to learn from examples provided in the prompt without weight updates. For example, giving 5 French-English translation examples in the prompt, then asking to translate a new sentence. Transformers excel at this task, pure SSMs struggle because they compress information into a hidden state.

- Associative recall

- Ability to retrieve specific information based on its relationship with other elements. For example, remembering that a character mentioned at the beginning of a long text is “the doctor” when mentioned again 10,000 tokens later. Transformers maintain explicit access to the entire history via attention, SSMs must reconstruct this information from their compressed hidden state.

The debate over the announced death of Transformers resurfaces with each new architecture. Since the emergence of Mamba and State Space Models (SSM) in 2023, apocalyptic predictions multiply on LinkedIn and at tech conferences. Yet, by late 2025, on-the-ground reality tells a more nuanced story. Hybrid architectures that combine attention and SSM are gaining ground, but not for the reasons we imagine.

Models like AI21’s Jamba, Zyphra’s Zamba2, or IBM Research’s recent Bamba don’t replace Transformers. They complement them in specific use cases where efficiency matters more than raw performance. 2025 benchmarks reveal a clear segmentation: hybrids excel on long inference and memory constraints, but pure architectures still dominate tasks requiring associative recall or in-context learning.

This distinction is not trivial. It redefines how we choose our architectures in production.

Memory in Sequence Models: Explicit vs Dynamic vs Routed

Targeted efficiency of hybrids: promises and reality

Attention-SSM hybrid architectures promise the best of both worlds: Transformer attention capacity and SSM linear efficiency. On paper, it’s appealing. In practice, gains concentrate on specific scenarios.

Jamba, AI21’s hybrid model launched in early 2024 and refined in 2025, illustrates this approach. With 52 billion parameters of which only 12 billion are active at inference thanks to a Mixture-of-Experts architecture, it combines Mamba and Transformer layers. The result: a 256k token context window with inference throughput superior to equivalent-size Transformers. IBM Research followed similar logic with Bamba, which reduces model size from 18 GB to 9 GB via 8-bit quantization while maintaining performance comparable to Llama-3.1 8B, despite being trained on seven times more data.

Efficiency gains are real and measurable. NVIDIA’s Nemotron-H, which replaces 92% of its attention layers with Mamba2 blocks, shows up to three times higher throughput than similar-size Transformers like LLaMA-3.1 and Qwen-2.5. This acceleration comes from a fundamental SSM characteristic: the absence of key-value cache. Where a Transformer stores the complete sequence history in GPU memory, the SSM maintains a constant hidden state, regardless of context length.

But this efficiency comes at a cost. Research published in July 2025 in “Characterizing State Space Model and SSM-Transformer Hybrid Language Model Performance with Long Context Length” shows that pure Mamba and Mamba-2 models lag significantly on benchmarks requiring strong associative recall or in-context learning, notably five-shot MMLU. Hybrids partially bridge this gap by reintroducing strategic attention layers, but don’t catch up to pure architectures.

This segmentation is not a bug, it’s a feature. Hybrids optimize for infrastructure and latency constraints, not absolute performance on all benchmarks.

Gated Attention: the incremental improvement that matters

While SSM hybrids capture media attention, a more discreet innovation transforms Transformers from within. Gated Attention, awarded Best Paper Award at NeurIPS 2025, represents exactly the type of incremental improvement that makes a difference in production.

Alibaba’s Qwen team demonstrated that a minimal architectural modification – adding a sigmoid gate specific to each attention head after Scaled Dot-Product Attention – systematically improves performance on models up to several billion parameters. This simplicity is deceptive. Experiments show that this gate introduces nonlinearity and sparsity in attention, reducing the attention sink phenomenon where certain tokens artificially accumulate attention without semantic reason.

Practical results are tangible. Gated Attention improves training stability of large language models and facilitates context extension. In extrapolation tests from 32k to 128k tokens with YaRN, models equipped with Gated Attention show less performance degradation than baselines. It’s not revolutionary, but it’s exactly the type of improvement that compounds: a few perplexity points less, better long context utilization, increased stability.

Rapid adoption of this technique is explained by its ease of implementation. Unlike hybrid architectures that require rethinking training and inference, Gated Attention integrates into existing pipelines with minor modifications. ML teams can add it to their Transformers without rewriting their CUDA kernels or adapting their serving frameworks.

This incremental approach strongly contrasts with the disruptive discourse around SSMs. It reminds us that improving existing architectures often remains more pragmatic than their complete replacement.

Benchmarks don’t lie: the superiority of pure architectures

Raw performance metrics tell a clear story in 2025. On tasks requiring complex reasoning, precise recall, or few-shot learning, pure Transformers maintain their lead.

The paper “Achilles’ Heel of Mamba” accepted as spotlight at NeurIPS 2025 identifies fundamental SSM limitations via synthetic data. Mamba architectures, despite their linear complexity and impressive performance on long sequences, systematically fail on copy and recall tasks that pose no problem for Transformers. This weakness is not an implementation detail that can be corrected with more data or better tuning. It stems from the very structure of SSMs, which compress information into a fixed hidden state instead of maintaining explicit access to the entire history via attention.

IBM Research results on Granite 4 confirm this pattern. Their tests show that “pure SSM models match or exceed Transformers on many tasks, but Mamba and Mamba-2 models remain significantly behind on tasks requiring strong copy or in-context learning capabilities”. This limitation appears notably on five-shot MMLU, where models must generalize from examples provided in the prompt.

Hybrid architectures attempt to circumvent this problem by reinjecting strategic attention layers. Jamba alternates Mamba and Transformer blocks. Zamba2 and Nemotron-H adopt similar strategies. But even with this approach, hybrids don’t systematically reach pure Transformer scores on standard academic benchmarks. They match on some metrics, exceed on others related to efficiency, but don’t dominate uniformly.

This reality forces us to rethink the debate. The question isn’t “will SSMs replace Transformers?” but “for which use cases are hybrid compromises acceptable?”. A chatbot handling conversations of several tens of thousands of tokens clearly benefits from SSM memory efficiency. A complex reasoning model on mathematical or code tasks needs full attention capacity.

Use case dictates architecture, not the reverse

The segmentation observed in 2025 pushes ML teams to reverse their architectural decision process. Rather than choosing the latest trendy architecture and adapting use cases, practitioners start from business constraints to select the right approach.

Long document processing applications – legal analysis, medical synthesis, code review – benefit from SSM-Attention hybrids. The ability to process 128k or 256k token contexts without exploding GPU memory fundamentally changes the economics of these use cases. IBM explicitly positions its Granite 4 models with hybrid Mamba-2 architecture to “reduce enterprise inference costs” rather than to beat records on academic benchmarks.

Conversely, complex reasoning tasks, code generation, or multi-hop question-answering continue to favor pure Transformers. GPT-4, Claude, or Llama family models maintain complete Transformer architectures precisely because their main use cases require this strong associative recall that SSMs struggle to reproduce.

This distinction also appears in optimization choices. Qwen’s Gated Attention improves existing Transformers without changing their fundamental nature. It’s evolution, not revolution. Teams that have already invested in Transformer infrastructure – optimized kernels, training pipelines, debugging tools – can adopt these incremental improvements without rebuilding everything.

The “Unified Factorized Framework” proposed in the paper “How Many Heads Make an SSM?” published in December 2025 attempts to formalize these trade-offs. It represents attention and SSM as instances of the same input-dependent interaction operator, with two distinct construction patterns: explicit mixing attention-style, and structured dynamics state-space-style. This theoretical unification suggests that the choice between the two isn’t binary but depends on task properties.

Teams that succeed in 2025 are those that test empirically rather than follow trends. They benchmark their real use cases on multiple architectures and choose based on metrics that matter for their product: P99 latency, cost per million tokens, quality on their private data. Public leaderboards on MMLU or HumanEval inform these decisions but don’t dictate them.

Evolution rather than revolution

The discourse on the “end of Transformers” rests on a fundamental misunderstanding of how architectures evolve in production. Architectural revolutions are rare. Incremental improvements compounded over several years are the norm.

2025 Transformers no longer resemble those of 2017. Grouped-Query Attention reduces KV cache size. Multi-Query Attention accelerates decoding. Flash Attention optimizes GPU memory usage. Gated Attention improves stability and reduces attention sinks. These modifications stack to produce substantial gains without changing the fundamental paradigm.

SSM-Attention hybrid architectures fit into this evolutionary logic. They don’t “kill” Transformers, they expand the space of available solutions. For certain use cases – ultra-long sequence processing under memory constraints – they become the optimal choice. For others – complex reasoning, few-shot learning – pure Transformers remain superior.

This coexistence is healthy. It forces researchers to clarify trade-offs rather than promise universal solutions. It pushes practitioners to measure empirically rather than adopt blindly. It creates competitive pressure that benefits both approaches.

Recent theoretical work, like the computational complexity analysis showing that Mamba and Transformers reside in the same DLOGTIME-uniform TC⁰ class, suggests fundamental equivalence despite architectural differences. This theoretical convergence reinforces the idea that the choice between architectures relates more to engineering – memory profile, latency, ease of implementation – than fundamentally different expressive capabilities.

The ML industry is maturing. It’s gradually emerging from the “hype cycle” phase where each new architecture promises to revolutionize everything, to enter a phase of pragmatic optimization where architectural choice becomes an engineering variable among others. Transformers don’t disappear in 2025. They evolve, specialize, and coexist with alternatives optimized for other constraints.

The real question for tech teams isn’t “which architecture will win?” but “which compromises are acceptable for our use cases?”. And this question, no academic benchmark can answer for us.

Quick Comparison

| Aspect | Transformer | SSM | Hybrid |

|---|---|---|---|

| Memory | O(n · d) | O(d_state) | O(n_local) + O(d_state) |

| Recall | exact | implicit | targeted |

| Streaming | poor | native | good |

Web Resources

- IBM Research - Bamba: SSM-Transformer Hybrid Model

- AI21 - Announcing Jamba Architecture

- Characterizing SSM and Hybrid Model Performance with Long Context (arXiv)

- NeurIPS 2025 Best Paper Awards - Gated Attention

- Gated Attention for Large Language Models (OpenReview)

- InfoQ - IBM Granite 4 Hybrid Mamba-2 Architecture

- AI21 - Attention Was Never Enough: Rise of Hybrid LLMs

- Understanding Mamba-Transformer Hybrids (arXiv)

- Achilles’ Heel of Mamba (arXiv)

- How Many Heads Make an SSM? Unified Framework (arXiv)

AiBrain

AiBrain